A walk on the wild side: mountains of Provence-

Do you also think of crisp air and high peaks when you hear “Provence”, or only of the olive trees and lavender fields, of the sun and the sea?

Of course, there’s the sea. We built these lands around the sea, we, the Romans, the Greeks, the Norsemen, the Arabs, the Gallic, we the Europeans, with our merchant vessels, our fishing boats and our amphorae filled with oil and wine. We were all irresistibly pulled to “her”, because obviously she’s female in our languages, the Mediterranean or “middle sea”, the Mother-Sea, the very core of our worlds. That’s why they call it the “Côte d’Azur” (azure coast, the French name for our Riviera), that’s why the whole world knows the pictures of our languid sunsets in the white harbors of our little towns, and of the glorious beaches, whose beauty means the beauty of the whole world to us.

For many years, I had only eyes for the sea. I was the kind of child who would have never come out of the water, if its parents had let it, who would have tried to reverse the process of evolution and crawled back to the mighty primeval ocean, as a mermaid or as another shimmering creature of the abyss. I was the kind of child who dreamt of shoreless oceans, and who could never understand Ariel when she meant that she wanted to be part of our world: why would you, Ariel? When you can fly through the depths as though they were the infinite sky of the sea?

A sunset in Saint Raphael’s harbor, after a long day hike in l’Estérel.

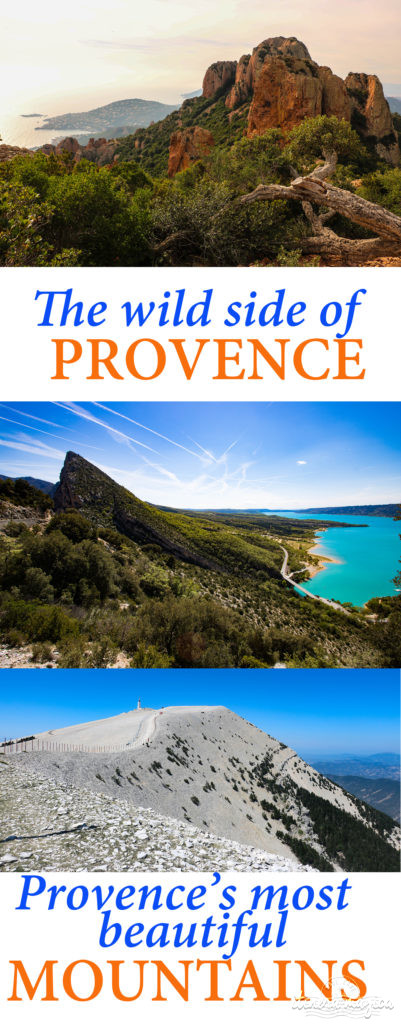

But there’s a turning point in every story, when the wanderer abandons the well-lit comfort of his home, and seeks the mountain. He might be reaching for higher summits or diving down in the deep, and he’s usually looking for God, the devil, or both, i.e. for himself, facing the dangers that lurk within. Provence’s mountains are the dark side of the moon, the unknown harshness beyond the softness of lavender fields. It always feels counterintuitive to turn my back on the sea and to drive towards the mountain – I feel so alien amid the crisp cold, the leafless peaks, the all-barring wind. I feel the mountain howling in my ear: you don’t belong here. I definitely don’t. I’m a good and confident swimmer, but as a mountain hiker, I always feel inadequate, especially when going down on rocky slopes and unsteady ground. I often trip and get scratch wounds on my palms and bruises on my bum, just like the clumsy children – most probably because the physical integrity of my camera matters more to me than my own, and that I willingly sacrifice myself. Provence’s mountains are treacherous and mean. I get along better with the Bavarian Alps, for instance, with their grassy glossy curves and convenient paths. The French do it French style: gibberish maps, washed out trail markings, shortcuts for daredevils, all summed up by the well-known phrase: “démerde-toi”, sort it out for yourself! But I keep coming back. Because the mountain strangely rewards me every time with its violent grace. Let’s take the proverbial walk on the wild side.

La Grande Corniche

One of the splendid panoramas awaiting those who drive the Grande Corniche road. The village on the rocky promontory is Eze.

I don’t feel ready to lose sight of the sea just yet. Let us stay in the region we call Alpes Maritimes: the seaside battalions of our great Alps. The “Grande Corniche”, which means “Great cliff road”, is probably the French riviera’s most iconic and beautiful road, rising up to 650 meters (2132 feet) above the sea, stabbing you in the heart with dramatic panoramas at every turn. Such heights and such lofty visions of the land and the sea thrown at your feet were meant to inspire megalomaniac emperors throughout the ages. This road was part of the Via Julia Augusta, leading Roman armies and chief leaders from the Latium to the faraway lands of Gaul. In La Turbie, a picturesque little village on the heights, one can see the ruins of the Tropaeum Alpium, built in the last years of the first century BC to celebrate the victory of Emperor Augustus over all the peoples and tribes of the Alps: the inscription in the white marble lists the forty-five peoples conquered by Rome. Nearly two thousand years later, Napoleon was (obviously) the one to rebuild this magnificent road, for every one of us tourists to feel now on top of the world when cruising on it.

If you drive this road, you absolutely need to stop in Eze: its magnificent castle and gardens could easily belong to a list of France’s most beautiful castles to visit.

La Turbie and its famous Roman monument, the Tropaeum Alpium.

One of the Riviera’s most beautiful villages, Roquebrune Cap Martin.

L’Estérel

With their blood red cliffs and deeply entangled forests – a scrubland of roots and thorns –, Estérel mountains were always France’s Wild East, an extremely perilous mountain range to cross for travelers on their way to Italy, throughout the centuries.

Red mountains and the bright blue sea, the kind of Technicolor landscapes l’Estérel rewards you with.

The Estérel range was rumored to be a real cut-throat: convicts who escaped from Toulon’s penitentiary found here a remote and intricate refuge, crooks and highwaymen lied in ambush beneath the pines and on top of the rugged promontories, attacking travelers passing by. “Malpey”, the old people of Provence used to call it: the bad mountain. These landscapes smell like danger. The jagged vermillion coastline, these rocky inlets where no boat can safely let go anchor, the sharp-crested ridges of the mountain range: everything here speaks of countless perils.

Wild wild Côte d’Azur.

One of the eighteenth’s century most famous bandits, Gaspard de Besse, hid in a cave by the Mont Vinaigre, and robbed rich foreigners travelling through the southern European lands. A dandyish outlaw, always wearing a red silver-buttoned suit, Gaspard de Besse took pride in never killing anyone, and was nicknamed the French Robin Hood for his generosity towards the poor. When he was betrayed by one of his men and lashed to the wheel in Aix-en-Provence, in 1781, dying at the age of 24, the whole people of Provence stood behind him and begged for mercy. “Provence’s greatest plagues are the state and the wind (mistral)”, Gaspard de Besse said, and many here would agree: this adventurous anarchist, whose head was pinned to a tree on the great road, remains popular in these lands. Some dreamers still look for his famed hidden treasure.

On top of Cap Roux peak.

I got lost in l’Estérel too often to feel unequivocal love for it, but I truly believe it to be one of Provence’s most striking mountain ranges, with its rough and ravaged beauty, its deep furrows telling of the relentless assault of the sea on the high walls of red stone.

La Sainte Victoire

La Sainte Victoire.

Mount Sainte Victoire owes the painter Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) its unquestioned status as Provence’s most iconic mountain. Cézanne’s works immortalized it unceasingly, in every season and at every hour of the day, like a Renaissance artist obsessed with the Virgin’s Mary glowing image, drawing her heavenly features on every altar and every rosary. When you live in Aix-en-Provence, as I do, with the mountain looming in the distance like an ancient goddess, with the great crucifix (“la Croix de Provence”) erected at its peak, catching the last sunset rays, ever visible, even in the deepest fog, the religious devotion slowly gets to you. This is THE mountain. All hail to Thee, Sainte Victoire.

The hike to the cross (Croix de Provence) is a tough, but popular pilgrimage even atheists will carry out.

Le Mont Ventoux

This is Provence’s other holy mountain: le Mont Ventoux, the silver haired guardian of the North, standing so alone and so high (1911 meters, or 6,273 feet) that it can be spotted easily from countless places in Provence, even at a distance of hundred kilometers, like the ever open eye of God. Many people believe the summit is shrouded in everlasting snow, which would account for its striking whiteness, and I thought so too for many years. But in truth, Mont Ventoux doesn’t owe its ghostly silhouette to snow, but to stones. Immense fields of countless white stones, covering the highest part of the mountain’s slopes, a barren landscape, entirely mineral, without a single tree – a wild and desolate region only Christian saints would venture in. This is a biblical mountain, a place for the overwhelming and the almighty.

Moon-like landscape.

Mont Ventoux means Windy Mount, and you only need to get there to understand why. Provence’s famous cold north wind, the mistral, reigns as a king, and blows continuously, stripping the summit of every vegetal and animal life. It feels like landing on the moon.

Where the trees recede.

The wind is often so strong that you can barely stand on your feet – on a stormy day back in 1967, its speed reached 320km/h (198 mph). The Tuscan poet Petrarca climbed the “Mons Ventosus”, its Latin name, back in the fourteenth century, and legend has it he was the first one to do so. He recounted his extraordinary adventure in a letter he sent to the monk Dionigio Da Borgo San Sepolcro in 1335, speaking in awe of wrestling light and darkness, of the most stunning view, of the sea of clouds at his feet. Countless other writers have stayed in Malaucène, the lovely village situated on the north flank of the mountain, and contributed to its mythical aura. I wish I had such inspiring stories to tell, but the truth is, Mont Ventoux is incredibly rocky and complicated to hike on, and I came back with bloody hands and a thirst for more amiable grounds, for grass, flowers and springs – for a less desolate kind of splendor.

Stonetides sweeping below your feet.

Les Gorges du Verdon

Verdon’s mountain range epitomize what we call the interior Provence – together with the Lubéron, about which I also wrote here (in German).

A storm over Verdon.

This is the other face of our sunny lands, far away from the sea, where the sun reaches the bottom of the deepest valleys only a couple of hours every day, where the winters get incredibly tough. We, the people living on the banks of the river Rhône or on the sea shores, we often don’t even know about this other Provence, the calm one, the brutal one.

Provence’s most famous writer, Jean Giono (1895-1970), lived and died in Manosque, a little town among those hills, and wrote panegyrics about the breathtaking Alpine landscapes, about the cold bright blue rivers tearing their way through the arches at the bottom of the deep canyons, about frost on the fields and snow on the peaks. Here people live at another pace, vulnerable and attentive to the seasons, waiting for spring to return.

A stormy afternoon.

Huge vultures inhabit these mountains, and I just can’t get used to my own feeling of admiration for the beauty of creatures which feed on corpses.

Their bald white necks, designed for plunging their heads into decaying carcasses without getting tainted. Their huge, dark brown wings, throwing a shadow on the milky blue river, thousands of feet underneath. Their ominous circling flight over the steep grey cliffs. I can’t keep my eyes off them.

Vultures in the grey sky.

Vultures flying above the canyon.

But the true objects of my undying fascination for Verdon’s landscapes are the river and the lake (Lac Sainte Croix), with their otherworldly shades of blue, their mazy ways meandering through the canyon, the waterfalls dripping down the mossy slopes.

Every time I see the lake appear, I have the feeling that I found a hidden gem, glistening at the bottom of the abyss, a seductive and dangerous promise of mystical delights to be found below the water surface. This is the kind of mesmerizing water antique heroes once drowned in, the kind that whispers “come to me” in your ear.

Hypnotizing Lac Sainte Croix.

Verdon is a spellbinding place where I always come back. And if you insisted and made me tell which mountain I like best, I would have to lower my voice, for the other mounts not to hear, since I fear their overwhelming shadows, but I would tell you: this is it.

The lake, as seen from Aiguines.

This is the secret magic that got me addicted, the only place that can shake my undying love for the seaside. But still, it’s because of the moving water, of the lake and the river: here lies, amid the sharp rocks, another dark mirror of Provence’s starlit night.

Lac Sainte Croix.

At that precise spot, the canyon is 700 meters (2296 feet) deep.

If you wish to discover further beautiful mountain ranges in Provence, check out this post about the idyllic coastal town Cassis.

Pin me!

mountains of Provence – mountain hikes in Provence – travel blog Provence

Did you enjoy this post?

Please share it or pin it!

-

To keep track of Itinera Magica’s travels, please like our Facebook page Facebook

or subscribe to our newsletter

Thank you for your support, and see you soon!

le 25 May, 2016 à 17 h 00 min a dit :

Love the photos! Weird, how France is always there, and I always want to go there, but then I never do. But after reading most of your article about the Provence, I might just go there sooner rather than later 🙂

le 26 May, 2016 à 12 h 01 min a dit :

Danke Nina! Du kannst dich sehr gerne bei mir melden, falls du irgendwann hierher kommst, ich helfe gerne weiter 😉

le 27 January, 2017 à 19 h 30 min a dit :

I’m kicking myself for not exploring France beyond Paris. Provence looks magical and you are so lucky to live there!

le 27 January, 2017 à 21 h 25 min a dit :

Thank you dear Flo! Come back whenever you like 🙂

le 27 January, 2017 à 21 h 16 min a dit :

Ah, what lovely places!! There is so much to explore in France – such a beautiful country. I visited Orange, once to see the ruins and it was a fantastic experience. I’d love to show the kids this ‘wilder’ side of Provence!

le 27 January, 2017 à 21 h 29 min a dit :

Thank you dear Natalie, Orange is an awesome place, I am so glad you enjoyed your stay in my home country, I hope you do come back 🙂

le 28 January, 2017 à 2 h 13 min a dit :

Your beautiful and poetic prose about the stunning area of Provence tugs at my wanderlust and heart strings!! I’d love to return to France and explore more, especially Provence. I had no idea it was like this!

le 28 January, 2017 à 22 h 00 min a dit :

Thank you so much dear Stephanie! It makes me happy that I could show you my home country !

le 28 January, 2017 à 6 h 28 min a dit :

What beautiful pictures and I absolutely love the personal touch to your writing!

le 28 January, 2017 à 22 h 02 min a dit :

Thank you so much, Robyn, this is really kind of you!

le 28 January, 2017 à 8 h 37 min a dit :

We drove down through the coast of France in Spring 2015. It was definitely one of the most enchanting places I have been to. At first I was totally opposed to renting a car. I thought it would be way to expensive but my husband was adamant. Today I look back at it and I am glad we did. You have a really beautiful country!

le 28 January, 2017 à 22 h 03 min a dit :

Thank you so much, Penny! I am glad you did, it’s really worth it 😉

le 3 September, 2019 à 11 h 10 min a dit :

What a stunning place! I wish I could spend a couple days here, breath the fresh air, out of the noisy city. Thank you for sharing the stunning town!

le 18 June, 2025 à 12 h 04 min a dit :

[…] © Itinera Magica […]